This page edited by a professional economist, Morris Silver, is devoted to the consideration of unsettled or disputed aspects of ancient economies, including the entire Mediterranean world. It builds on my books Economic Structures of Antiquity (ESoA) (1995) Greenwood Press, Westport, Connecticut, and Taking Ancient Mythology Economically (TAME) (1992), E.J. Brill, Leiden. The page also incorporates my own more recent research as well as contributions submitted for the page by interested scholars.

The page was last revised on November 4, 2008.

Review of James P. Allen, The Heqanakht Papyri (2004) [Published by EH.NET (2004)]

Review of David M. Schaps, The Invention of Coinage and the Monetization of Ancient Greece (2004) [Published by EH.NET (2004)] and "Postscript" (added May 17, 2004; revised September 3, 2004)

Review of

Walter Scheidel and Sitta von Reden (editors), The Ancient Economy (2002) [Published by EH.NET (2003)]

In progress: Some notes concerning the ashera. Last revised May 9, 2003

Content of TOPIC I

Introductory

Remarks

A.

Mesopotamia

B. Ebla

C.

Hittite Anatolia

D.

Ugarit

E.

Israel

F. Egypt

G.

Mycenaean Greece

H.

Dark Age Greece/Archaic Greece

The question has not been posed as "Did the ancient Mediterranean world know

private merchants?" because rulers and officials who engaged in commercial

activities may or may not have been public enterprisers in the sense that their

enterprises with their profits belonged to the "public," that is, to the nation

at large. To illustrate, in about the middle of the second half of the second

millennium, the ruler of Cyprus, in requesting payment for a shipment of lumber,

complained to Pharaoh that "the people of the land murmur against me"

(Liverani). Why did the people "murmur"? Were the "murmurers," so to speak,

"stockholders" in a royal export enterprise? Or were they independent merchants

who had not received payment for their lumber and asked their king to intercede

with Egypt's king in their behalf? (For a preliminary discussion of public

enterprise in antiquity, see ESoA, Chap. 3.)

Click here for full size image

It is true and unsurprising that officials of palace and temple [and aristocrats e.g., Charaxos of Lesbos, Sostratos of Aigina, Phobos of Phocaia, and Solon (?)] played major

roles in the commercial life of the Mediterranean world. In practice, the

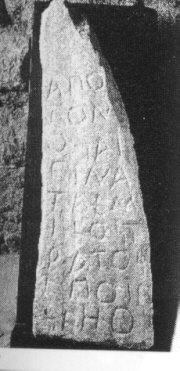

Half an anchor from Gravisca dated to the end of the 6th century. The dedication is from Sostratos to Apollo. This Sostratos is probably to be identified with Sostratos son of Laodamas whose fabulous profits from trade are mentioned by Herodotus (4.152.3).

The entrepreneur is an individual who has acquired some familiarity with the preferences and economic opportunities of distant markets and has access to capital to implement his insights. Today a variety of socioeconomic roles prepare an individual to be an entrepreneur, but in antiquity the appropriate roles would have been much more limited to officials and members of the elite. The point is that given the relatively limited pool of entrepreneurial talent, a major role for palace and temple is predictable. Nevertheless, there is a significant body of evidence pointing to the existence of independent merchants, some of which is outlined below.

1. In the cycle of stories about the Kings of Akkad, we find one (in an Akkadian tablet from Amarna and in Hittite fragments), called "King of Battle," in which merchants who are obviously independent, petition Sargon (2334-2279), the founder of the Dynasty, offering to pay his expenses to open the trade routes to the north and northwest.

2. In late third millennium Sumer (Ur III) merchants (damkar's) do not appear on royal "ration lists" and their seals do not depict royal presentations. Certainly, as the "balanced account documents" documents demonstrate, merchants acted as agents for the palace, but it would seem that these traders were not members of the bureaucracy or simple employees of the crown. On the other hand, there is little if any direct and unambiguous evidence of independent commercial activity. However, Neumann (1999: 53) cites a loan document from Nippur in which a merchant declares that he will repay the amount lent "if he gets back from his commercial journey (kaskal)." I would agree with Neumann that this promise strongly suggests both independent finance and commercial activity. Neumann, Hans. (1999). "Ur-Dumuzida and Ur-DUN." In Dercksen (ed.), Trade and Finance in Ancient Mesopotamia, 43-53.

Envelope for tablet from Assyrian trading station in Cappadocia

Envelope for tablet from Assyrian trading station in Cappadocia

3. A mountain of evidence demonstrates that the Assyrians trading in Cappadocia in the early second millennium were basically independent businesspersons, not agents of temple or palace. Thus, for example, a great merchant complains in a letter that he was losing much profit because of delays in obtaining a loan to finance an enterprise (ESoA, p. 168). At roughly the same time the Persian Gulf trade of Sumer with Tilmun (Bahrain) was in the hands of nonroyal merchants who styled themselves alik Tilmun or "go-getters of Tilmun."

4. For the Old Babylonian period (ca. 2000-ca. 1600) there is much evidence of nonroyal commercial activity and little evidence connecting merchant (tamka_ru) with palace. One example of independent commercial activity is of special interest. In two liver omen texts one Kurû, probably to be identified with Kurû the tamka_rum attested in contemporary texts, makes sacrifices of lambs in order to foresee whether his affairs will prosper.

Both texts refer to prospective sales in the market: ina su_qi_ ši_ma_ti, literally, "in the buying streets ... One of these texts asks whether Kurû is going to make a profit (ne_melu) on some kind of (gem?) stone, whereas the other asks the same about the sale of goods, "market/trade goods", sachirtu ... (Wilcke cited by Powell 1999: 11)Powell, Marvin A. (1999). " Wir müssen alle Nische nutzen: Monies, Motives, and Methods in Babylonian Economics." In J.G. Dercksen (ed.) Trade and Finance in Ancient Mesopotamia. Leiden: Nederlands Historisch-Archaeologisch Instituut te Istanbul, 5-23.

5. In the mid-second millennium at Nuzi in eastern Assyria tamka_ru appear on royal "ration lists," but nonroyal individuals also employed their services. Some Nuzi texts show merchants borrowing from independent lenders for business ventures. A lawsuit concerning a merchant who disregarded a royal proclamation fixing a maximum price on slaves also attests to self-employed merchants.

6. Evidence of commercial activity is sparse in Babylonia after the Old Babylonian period and becomes more plentiful again in the later second millennium. Large nonroyal commercial houses flourished from the seventh to the fourth century BCE. The House of Egibi, for example, bought and sold houses, fields, and slaves, took part in domestic and international trade, and participated in a variety of banking activities.

At Ebla in northern Syria in the mid-third millennium, according to Pettinato, the lu-kar "man of the commercial center" is an independent businessman and the kas or lu-kas "messenger" is a royal merchant.

My evidence for nonroyal Hittite merchants is sparse and somewhat ambiguous.

Paragraphs 5 and 6 of the Hittite Laws* require that if someone kills a

traveling Hittite merchant he must pay compensation and replace the goods of the

merchant. If seen in the context of similar provisions in the Laws, we have to

understand that the payments are due to the merchant's family or partners, not

to the king. (This interpretation finds support in a letter dating to the

thirteenth century from a Hittite ruler to a Babylonian ruler concerning

compensation for murdered merchants.) A merchant who owns his own trade goods is

to this extent independent. An edict of the Hittite king to the king of Ugarit

(see below) says that citizens of Ugarit who fail to repay their debts to

merchants from Ura (an important port in Cilicia) should be handed over to them

(as slaves). There is no indication that the merchants of Ura are doing business

in Ugarit on behalf of the Hittite king.

*For a recent translation of

the Hittite Laws, see Harry Angier Hoffman (1997). The Laws of the Hittites:

A Critical Edition. Leiden:Brill.

Texts from Ugarit (ca. 1400-ca. 1200), an important north Syrian port, demonstrate individual ownership of cargo ships and also show individuals, including merchants (mkrm), paying large sums of gold for trading concessions and the authority to collect harbor taxes. (In one instance the king of Ugarit declared a vessel to be exempt from duty when it arrived from Crete.) A treaty between the rulers of Ugarit and a neighboring state permitted citizens to form partnerships (tapputu) for commercial expeditions to Egypt. One text refers to an individual about to undertake a voyage to Egypt with the financial backing of four persons. Some merchants with no explicit royal connections spoke of "my merchants" and the merchants "of my hand." ("Merchants of the hand" are attributed to Tyre in Ezekiel 27.15,21.)

Heltzer has gone beyond this relatively clear evidence of nonroyal business enterprises. He believes that Ugarit knew two categories of merchants: tamkaru sha shepi, who were dependents of the king, and tamkaru sha mandatti, who clearly possessed their own trade goods and for whom there is no direct evidence that they traded with palace goods rather than their own. Heltzer's interpretation has, however, been criticized by Vargyas who suggests, among other points, that mandattu may denote private property or royal property.

The Bible records the joint trading expedition of Solomon and Hiram the king of Tyre to Ophir for gold, sandal-wood, and precious stones (1 Kings 9.26-28; 10.1) and the purchase of horses by "the king's merchants" (sochare ha-melek) from the "men of Kevah" (1 Kings 10.28). But the Bible also provides evidence of nonroyal merchants in Solomon's time (tenth century). 1 Kings 10.15 takes note, in Gray's translation, of that portion of Solomon's gold originating in "the taxes (tolls) (`onshe) on the merchants (tarim) and the traffic (missahar) of the traders (roklim) of all the kings of the arabs and the governors of the land." This translation requires a number of emendations of the Massoretic text, most importantly `onshe for 'anshe "men." (Dahood identifies 'anshe with Ugaritic unt "tax, dues.") Although the historical value of the text may well be disputed, it does seem possible, assuming 'anshe/`onshe = "tax, toll," that Israel had two classes of merchants: roklim (and sochare ha-melek), who served kings, and tax-paying tarim (and sochare?), who were basically independent merchants.

Was trading, at least larger scale trading, a virtual royal monopoly? There is evidence suggesting otherwise.

ADDITION (11/23/97): The evidence summarized below is derived mainly from New Kingdom sources. I have not yet found strong evidence of specialized nonroyal merchants for earlier periods. There is, however, evidence of noninstitutional commercial activity. There are marketplace scenes on Old Kingdom tombs, one of which shows traders selling cloth (ESoA, p. 162). That an individual might own a cargo-boat is suggested by the inscription of Qedes of Gebelein dating from the late third millennium (First Intermediate Period) (ESoA, p. 57). In a text dating to early in Dynasty Twelve, Hekanakht refers in routine terms to renting, buying and selling land, cloth, oil and whatever (ESoA, pp. 173-74). Hekanakht, obviously acting as an individual, may or may not have operated on a large scale, but the demonstrated existence of a market leaves open the possibility that others did. In an ane list message (11/22/97), Lorton takes note of "The Eloquent Peasant"*: "The story is set in the First Intermediate Period, though it could be debated whether this or the Middle Kingdom is the actual date of its composition. Also ... this is a work of literature. Thus, it is uncertain whether the tale's protagonist, an itinerant merchant, is the product of verisimilitude or the desire of the writer to add an outrageous detail." *For a translation of The Eloquent Peasant, see Miriam Lichtheim (1973), Ancient Egyptian Literature, Vol. I: The Old and Middle Kingdoms, University of California Press, pp. 169-84.********

1. In the early fifteenth century the god Amen delivered an oracle to the ruler Hatshepsut concerning the status of the incense trade. According to the oracle Hatshepsut would be the first ruler whose forces would tread on the incense terraces. Previously only sementeyew] had penetrated the "God's Land" and carried incense back to Egypt. Evidently the sementyew "man with a sack" was not a royal trader. Perhaps he was not a "large scale" trader, but we do not know this.

Altenmüller suggests, citing Yoyotte, that the sementeyew's are officials because they are structured into ranks. Even if true, this would hardly be a decisive consideration. (The undoubtedly independent Assyrian merchants in Anatolia were structured into ranks.) In fact, as Yoyotte notes, a strong connection with Old Kingdom rulers is demonstrated by such titles as "director, controller, chief, inspector" of sementeyew's. (Sementeyew also serve as "interpreters" and "vessel captains.") Indeed, in the later Old Kingdom, a "captain" led an expedition of quarrymen and sementeyew on behalf of a ruler's pyramid complex. A royal connection is clearly demonstrated by a New Kingdom tomb inscription from the time of Hatshepsut designating an official as "sementeyew of the king" (Yoyotte). On the other hand, the attribution "of the king" is redundant if sementeyew's were exclusively royal officials or agents. Further, Amen's oracle to Hatshepsut (cited above) gives the impression that the sementeyew's were outside royal purview. A final straw in the wind hinting and independent role is provided by the dedication of Sesostris I (1971-1926) to the Tod temple. Sesostris groups the marvelous contributions of the sementeyew's with those of foreign peoples (Yoyotte). Certainly the "foreign peoples" are not agents or employees of the Egyptian king!

2. In extolling the life of the scribe, Papyrus Lansing (4.8-10), a text dated to 1350-1200, recounts that "the merchants [shewtyew] fare downstream and upstream and are as busy as copper [see TOPIC III.4], carrying wares (from) one town to another and supplying him who has not, although the tax-people carry (exact?) gold, the most precious of all minerals" (Blackman and Peet; Caminos; Castle). [Menu has recently related shewety to shewet and translates it literally as "the one of the lack".] There is no indication whatever that the busy shewtyew are royal merchants. Moreover, if the merchants were subject to the tax-collector it is hardly possible that they were royal employees. Of course, the text does not specify that the gold "carried" by the tax-collectors was exacted from the shewtyew. But what then, in a composition dedicated to the advantages of the scribal profession, would be the point of the contrast between merchants and tax-collectors, and from whom did the tax-people obtain the gold?

3. Papyrus Lansing (4.10) continues with the observation that "the ship's crews of every house (per) they take up their freights. They depart for Syria." It is well known that, for good reason, the terms "family," "house," and "firm" overlapped in antiquity (ESoA, Chap. 2.D). Obviously, then, there were nonroyal trading "houses" operating in Egypt, Perhaps, the reference includes trading enterprises under the auspices of temples, but there is no reason to exclude independent firms. Another text (Pap. Bibl. Nat. 211.18) locates a merchant in the "house" of the scribe of contracts Mery (Janssen). Sike, chantress of (the god) Thoth, instructs her correspondent to go to the "merchant" (shewty) and have his oath annulled (Caminos, p.26). The point of Sike's letter is obscure but the merchant has no named institutional connection.

4. That an individual might own a cargo vessel is hinted in the late third millennium by the inscription of Qedes of Gebelein and proven by the Edict of Horemheb dating from the second half of the fourteenth century. Papyrus Leiden 344 (The Admonitions of Ipuwer) in pursuing its theme of reversal of fortune attests to the private ownership of ships : "Behold, he who never built for himself a boat is (now) the possessor of ships, he who possessed the same looks at them, (but) they are not his" (Shupak). There are also Ramessid texts in which individuals pay for the use of cargo ships. Papyrus Anastasi IV demonstrates that even a sea-going vessel was not beyond the means of a rich man. A rich man is represented as using his ship to bring goods from Syria to Egypt. Castle notes that

while the document is a panegyric rather than an administrative document, it may be argued that the scribe is obliged to paint his complimentary picture within the limits of what was socially possible. No office is attributed to him [the wealthy individual], although this might be expected in a panegyric if he were understood to hold some official position.

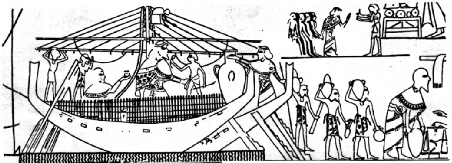

Click here for full size image

5. A text from Ugarit records the transfer of oil to "Abrm of Egypt." The account of Wenamun provides strong hints that Syrian trading houses were operating in Egypt in the later eleventh century.

6. The "Tomb Robbery Papyri" of the twelfth century include many references to shewtyew whose affiliations, if any, remain unstated. That these merchants were independent is suggested by the fact that "the scribes are otherwise particular in referring to the affiliations of witnesses for purposes of identification" (Castle). Similarly, an earlier document, Papyrus Boulaq 11, probably dating to the Eighteenth Dynasty, provides no affiliations for merchants who purchased meat and wine and, in one instance, paid in gold to the tune of 2.5 shat (see Topic III.4).

7. In Ostracon Wente, dated on various grounds to Ramessid times, one Menena instructs a police official named Menetjew-mes to sell the oil he had sent him in the marketplace (mereyet) (Allam). There is no indication that either individual is acting in behalf of the ruler. It would seem that Menena is a merchant. With respect to his policeman-partner, Allam notes that it is not at all uncommon for officials to have businesses on the side.

It will be objected that the above evidence does not conclusively demonstrate the existence of independent merchants in Egypt. Probably not. May we hope for a text which states that an individual was a merchant who was NOT employed by palace (or temple) and shows that he operated on a "large scale"?

A less intellectually self-serving line of objection is that the examples

cited come from periods of weak central government, when reality did not fit the

model of royal domination of resource allocation. This line of argument deserves

analysis. The emergence of independent merchants in periods of weak central

government shows that the necessary commercial mindset and entrepreneurial

talent lurked just below the surface of Egyptian society. The prevalence of the commercial mindset is strongly hinted in the Egyptian wisdom literature of the Middle Kingdom and New Kingdom by repeated condemnations of and warnings against the desire to acquire wealth and expressions of individual initiative.

For examples, see Bleiberg, Edward. (1994). "'Economic Man' and the 'Truly Silent One': Cultural Conditioning and the Economy of Ancient Egypt." Journal of the Society for the Study of Egyptian Antiquities, 24, 4-16. The negative attitude expressed toward entrepreneurial values in the wisdom literature does not, as Bleiberg believes, demonstrate that the Egyptian economy did not know markets.

Why then did not the

merchants come to the surface in periods of strong central government? One

possibility is that royal enterprise, perhaps as a result of economies of scale

and/or the favor of the gods, was much more efficient (i.e., had much lower unit

costs) than independent enterprisers. I find this line of explanation extremely

unlikely. The other answer is that strong central governments suppressed

independent merchants with a combination of confiscatory taxation, regulation

and naked force. Do we have evidence of such policies?

Speaking of the 18th Dynasty, Helck maintains that "foreign merchants, mainly from Phoenicia, were compelled to sell their more valuable goods to state institutions" (emphasis added). Of course, it is possible to visualize situations in which forced sales and monopolistic resales by the state would be a more efficient method of extracting monopoly rents than taxes alone. The problem is that the only evidence cited by Helck is a tomb-painting showing Phoenicians selling their "higher valued merchandise such as slaves, Syrian bulls or metal vessels" to Kenamun "mayor" of Thebes.Part of the tomb painting is displayed above.) This scene is simply incapable of demonstrating that "foreign merchants could not sell their goods to the people of Egypt directly but had to conform to the Egyptian state economy of this period."

Interestingly, we do seem to have an example of the central government seeking to suppress market behavior by its own officials! In the Nauri decree, Seti I (1306-1290) forbids officials from seizing for corvée the personnel of the Osiris temple in Nubia. But he also forbids them from hiring-away the temple's employees. The phrase used in the decree is m brt "by agreement/contract," which Kitchen relates to West Semitic berit "contract/covenant."

Then again, the entire argument is very far from being conclusive. It may turn out that most of the evidence for independent merchants cannot be demonstrated to come from periods of weak central rule. To determine this we need to date the evidence and lay it against the strength of central government. But how precisely can Egyptologists date literary texts such as Papyrus Lansing and Papyrus Anastasi IV? Further, care must be taken in identifying periods of royal weakness. For example, in the late Ramessid era the central government was apparently in disarray, but this would not seem to apply to the era of affluence culminating in the reign of Ramesess III in the later twelfth century.

Linear B tablet from Pylos.

Linear B tablet from Pylos.

Mycenaean Crete and mainland Greece, which, for good reason, have become the last stronghold of the "redistributional economy" and the epitome of the palace economy. With respect to the palatial economies of the mid-second millennium, it is well to note the limitations of the evidence provided by the Linear B tablets. The main archives from Knossos and Pylos cover only one year and do not cover significant sectors of the regional economy. Thus, for example, Palaima has pointed to the paucity of references to potters and he suggests that "This must imply minimally that the production of ceramic pottery was not centrally controlled directly by the centralized record-keeping administration, at least not in any way comparable to those economic activities which do find their ways into specialized series of Linear B tablets." Moreover, several Linear B tablets document trade. Most importantly, one tablet from Pylos (An 35) shows a trader, named a-ta-ra, receiving wine, wool and other goods from the palace in exchange for the imported mineral alum, used in building, leatherworking, and cloth dyeing. The a-ta-ra may well be an independent merchant.

Attached as an Appendix is Judith Weingarten's translation of extracts from

J.-P. Olivier "Des extraits de contrats de vente d'esclaves dans les tablettes

de Knossos" (1987). This important article strongly suggests the existence of

formal contracts and market activity outside the palace economy. See "Contracts..."

H. Dark Age Greece/Archaic

Greece

The classification of the undertakings ("labors") of the mythical hero

Herakles may cast light on commercial practice in Greece prior to the Classical

period.* On behalf of king Eurystheos, Herakles undertook various "commissions."

The Greek technical term here rendered as "commission" is athlos (or

aethlos) whose basic meaning is "activity carried out for a prize." The

Homeric Hymn to Herakles (15.5f) explains further that Herakles

"wandered" ("circuited" probably comes closer to the mark) doing "the bidding of

Eurystheos, and himself did many deeds of violence and endured many"

(Evelyn-White). But some manuscripts read aethleuon krataios "mighty

(difficult?) commissions" and exocha erga "outstanding works." Similarly,

Pausanias (3.17.3) mentions "the numerous labors of Herakles and numerous good

deeds he did of his own free will [ethelo_n]..." (Levi). Thus, it is

possible to understand that in addition to commissions undertaken on

behalf of Eurystheos and other principals, Herakles acted on his own behalf.

Like the merchants of the Near East, Herakles might be both principal and agent.

By far the most commercially revealing of those activities Herakles carried

out on his own behalf took place during his commission to remove the dung from

the cattleyard of Augeios, ruler of Elis. A legal dispute arose because

Herakles, despite his status as Eurytheos' agent, made a side-deal with Augeios

for a tenth

Herakles. Detail from amphora c. 485 BCE

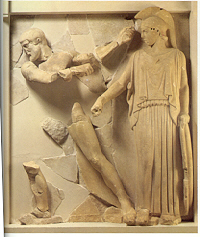

Metope of the Cleansing of the Augean Stables from temple of Zeus at Olympia. 5th century

of the cattle. When Augeios learned of Herakles' athlos for

Eurystheos, he refused to pay the contracted-for tenth. For his part, Eurystheos

refused to credit Herakles with a fulfilled commission because his activity "had

been performed for hire" (Ap. 2.5.5). The details of the dispute, as we have

them from Apollodorus, are at once trivial and obscure. Light seems to be cast

on the point of the matter by Babylonian long-distance trading contracts of the

seventh-sixth centuries wherein the principal stipulates how much of his capital

his agent might employ for traveling expenses and, more significantly, prohibits

the agent from doing business on the side. The myth suggests that similar

contracts were employed in Greece and that Herakles, as Eurystheos' agent, had

violated the no-side-business provision.

For an extended analysis of

the commercial aspects of Herakles' career, see Silver, TAME, Chap.

5.

ANE evidence demonstrates that commercial agents might be designated by words literally meaning "image, likeness." This simple finding, interesting in itself, provides a foundation for reinterpreting a broad range of ANE and Greek texts.

A clear example of this practice is found in Akkadian business documents of

the early second millennium Assyrian trade in Cappadocia (see TOPIC I.A.3). Here

we find the expression sha kima (Personal Name), meaning

"representative of PN" but literally "likeness of PN." This is of

course a perfectly reasonable idiomatic usage.

Some Implications

1. Sarna notes the use of "image" in regal vocabulary which "serves to elevate the king over the ordinary run of men" and he cites several examples:

In Mesopotamia we find the following salutations: "The father of my lord the king is the very image of [the god] Bel (salam bel) and the king, my lord, is the very image of Bel"; "The king, lord of the lands, is the image of [the god] Shamash." ...In Egypt the same concept is expressed through the name Tutankhamen (Tut-ankh-amun), which means "the living image of (the god) Amun," and in the designation of Thutmose IV as "the likeness of Re."Examples from Egypt might easily be multiplied, but one instance is especially supportive of the "agent as image" hypothesis: Ramesses II is called the "image (twt) of the sun god's right eye" (Hornung cited by Curtis). Obviously the intention is not to suggest that the king bears a physical resemblance to the eye of the god.

2. The principal/agent connection seems clear in an exorcism text: "The exorcism (which is recited) is the exorcism of (the god) Marduk, the priest is the image [tsalmu] of Marduk" (Clines citing Thompson).

3. Now I am ready to take up the much discussed problem of the relationship between man ('adam) and God's tselem "image" and demut "likeness." The traditional gloss for the be-preposition prefix is "in," so God created man "in His image" (Gen. 1.6-27; 5.1; 9.6) or "in His likeness" (Gen. 5.1). These renderings raise an anthropomorphism that is usually explained away by suggesting that bes.elem must be understood figuratively to mean that man is God's agent in the world. Thus, Callender (2000: 26-8) notes that tselem and demut refer to physical likeness: "But physical similarity should not be taken superficially; its intent is to express some deeper reality" and he cites Near Eastern evidence supporting the "notion of image as representative or viceroy." [Callender, Dexter E., Jr. (2000). Adam in Myth and History: Ancient Israelite Perspectives on the Primal Human Condition. Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns.]

On the other hand, in Gen. 1.26 we find the ke-preposition prefix with

"likeness." The traditional gloss for ke is "as," so "as God's likeness."

In addition, Gen. 5.3 says that Adam begot

a son bidmuto ketsalmo "as

his image" and also "in his likeness." The be/ke alternation

raises the suspicion that in the context of creation both preposition prefixes

mean "as."

Loren Crow informs me that bet essentiae is a well established use of the be-preposition. Chaim Cohen, to whom I owe special thanks, explains that "As regards bes.elem, I think that the meaning 'in His image' and 'as His likeness' is virtually the same." Given the number of examples where the regular usages of bet do not work, he thinks that bet essentiae is not needed here. (Compare also J. Maxwell Miller.)

The point, at last, is that "God created man as His image/likeness = "agent" is the literal (idiomatic) meaning of the biblical passages. This line of understanding is confirmed in Gen. 3.5,22 where man "will be like divine beings who know good and bad" or "man has become like one of us, knowing good and bad." The knowledge of good and bad and "opened eyes" are, of course, qualifications for any effective agent (see Sarna, Sawyer).

4. A more subtle and controversial example is provided in the Bible. I find it difficult to believe that Israelites in the time of Ezekiel or of Manasseh placed idols in or around the Jerusalem Temple. The key is the idiomatic meaning of the rare Hebrew word semel "image, likeness." (Myers translates semel in 2 Chron. 33.7, 15, concerning Manasseh, as "slab-image"; 2 Kings 21.7 uses instead the word pesel translated as "graven image.") The phrase including semel in Ezekiel 8.3 has been translated as "seat of the image of jealousy that provokes jealousy" or as "seat of the infuriating image that provokes fury." Torczyner notes that môshab "seat" is nowhere else in the Bible used for the pedestal or slab of an idol. The central phrase is sml hqn'h hmqnh in which, as Lutzky points out, "the relation between hqn'h and hmqnh is ... merely one of repetition of the same word in another form, but with the same meaning." The word hmqnh is not included in 8.5 which refers to "this image of jealousy." Some commentators consider hmqnh to be a later gloss to clarify the meaning of "image of jealousy." But how does it clarify? I propose the translation "seat of the commercial agent." It is well known that, for reasons of economic efficiency, ancient temples were commercial centers (see ESoA, Chap. 1). The rage of Ezekiel and his circle at the presence of a commercial agent in the courtyard of the Temple would be explained by their well-documented loathing for commercial life.

This line of interpretation finds support in the LXX and Old Latin versions which may be translated as "statue/image of the trader/buyer." [The phrase in the LXX is e_ ste_le_ tou kto_me_non, where ste_le "pillar, (inscribed) monument" [LSJ s.v.] is understood to mean "statue, image."] In 1942, C. Virollead suggested that the Greek and Latin translators used a different Hebrew text which included the expression "semel haq-qôneh ..., a word which resembles the other (hqn'h), but which is a totally different term, belonging not to the root qn', but to the verb qnh ..." (Lutzky's translation). The root qnh has such meanings as "acquire," "buy," "produce," and "(pro)create" (see Lutzky). For a recent summary of the linguistic issues, see Blomquist, Tina Haettner. (1999). Gates and Gods: Cults and City Gates of Iron Age Palestine, An Investigation of the Archaeolgical and Biblical Sources. Stockholm: Alqvist and Wiksell, 169-74.

Perhaps this is not, however, a case of the corruption of the Hebrew text that has come down to us. It is quite possible that Ezekiel used the root qn' "be jealous" instead of the similar root qnh in order to cast trading activity in a derogatory light. The ancient translators understood the nature of this play on words, but later commentators, often obsessed with idolatry, missed the point.

The plot thickens! In 1946 Torczyner noted that the word semel "inevitably brings to mind the Akkadian term shamallu_(m), meaning the commercial agent ..." This, he maintained, is no matter of accidental similarity. The older form of shamallu is shamala which

is no substantive originally, but the relative clause sha mala, with the meaning of sha kima [see above] (he who is as much as, he who represents and fills the place of the merchant). As a matter of fact, sha mala and sha kima are equivalent expressions to indicate the representative or agent of the merchant who, juridically, is the alter ego or the same as himself. (Torczyner)Torczyner suggests that the compound term sha mala was transmitted from Assyrian (not Babylonian) into Hebrew as semel, with sh being pronounced as s. Thus, again, the "image of jealousy" whose presence in the sanctuary enraged Ezekiel was a businessman, not an idol.

5. Greek mythology exploits the fact that words like epieikelon, therapo_n, eido_lon, psyche and skia might mean "physical likeness, representation, statue" or "agent." Note here Stesichorus' peculiar claim that not Helen but a "phantom" accompanied Paris to Troy. Again, in Il. 1.265 we find that the Attic hero Theseus was epieikelon athanatoisin "in the likeness of the immortals." Outside mythology we discover in two Linear B tablets from Pylos concerned with land ownership a te-seu "Theseus" who is termed "servant (do-e-ro) of the god."

6. Luwian hieroglyphic Kululu lead strip No. 2 dating from the earlier first millennium

records the distribution of sheep to four groups of recipients marked by the presence of "statues" in each group. The most noticeable feature of this text is that the "statues" themselves appear as the recipients of sheep together with the personnel attached to them...(Uchitel citing J.D. Hawkins)But were the recipients of sheep really statues or were they agents for the various cities named in entries 3, 12, 14, and 17? The word translated as "statue" by Hawkins is taru(t). Significantly, in entry 5 sheep are given to a tarpali-, a word translated as "substitute" or "representative" by Hawkins (see Hawkins 1987, pp. 148-50). It seems clear enough that we are dealing with agents not statues.

7. In Enuma Elish (I 16), the Creation Epic, we find that "(The god) Anu begot in his image/likeness (tamshilu) (the god) Nudimmud" (Clines, Tigay). However, in the absence of information about the relationship between the two gods it is difficult to make anything of this.

8. According to the Sumerian King List, the father of Gilgamesh was a lillû. Wilcke notes that lillû corresponds to Akkadian zaqiqu, meaning "phantom. ghost" (see CAD s.v.). Are we being told that the father was an agent?

9. In the Sumerian myth of Enki and Ninmah, the lesser gods lament loudly about having to serve the greater gods by performing such tasks as carrying vats, digging canals and grinding. Mankind is created to assume the unpleasant duties of the lesser gods. This solution is inspired by the following suggestion made to Enki by the primeval mother Nammu: "Fashion the kin-sí of the gods, may they throw away (?) their vats" (line 23). The word kin-sí which (apparently) is not attested elsewhere is often rendered as "substitutes" (Benito). However, the meaning "image, likeness" = "agent" fits the context rather nicely.

|

Ancient History: A Useful General Site Offering a Free Newsletter

|